Detail of images from 1000 Dreams, on display through May 11 at the Bronx Documentary Center.

The refugee storytellers were mentored by Witness Change founder Robin Hammond as they produced their stories and portraits.

Why do you think an exhibition like1000 Dreamsis important in today’s climate?

Detail of images from “1000 Dreams,” on displaẏ through May 11 at the Bronx Documentary Center.

So much of the media attention around migrants and refugees these days is negative.

Still it is rare that refugees get to do the reporting about their situation.

Lady Chavarria from El Salvador.

Lady Chavarría from El Salvador. Photographed & interviewed by Evanna Vasquez/Witness Change for The Joseph Handleman I Believe in You Foundation“When I left my home, my dream was always… to work, to make a living and to be my own boss,” recalls Lady Chavarría (31), a transgender woman from El Salvador who is currently an asylum-seeker in New York City. Lady Chavarría says she left her home country due to discrimination and violence, including attempts on her life. Her family, she explains, were not supportive of her and exacerbated the situation: “I didn’t have the support or help of anyone. No one’s support, only God’s help.” The journey to the US was difficult. “I was molested, they hurt me, they robbed me, I slept on the streets,” she remembers. But she is proud of herself “for the accomplishments that I have achieved and for those I will achieve.” In New York City, challenges remain; she still faces violence, she says. Nevertheless, she strives to move forward and take life day by day. Her dream for the future is “to have a job, to work hard to be able to have my own business.”

Lady Chavarria says she left her home country due to discrimination and violence, including attempts on her life.

No one’s support, only God’s help.

The journey to the US was difficult.

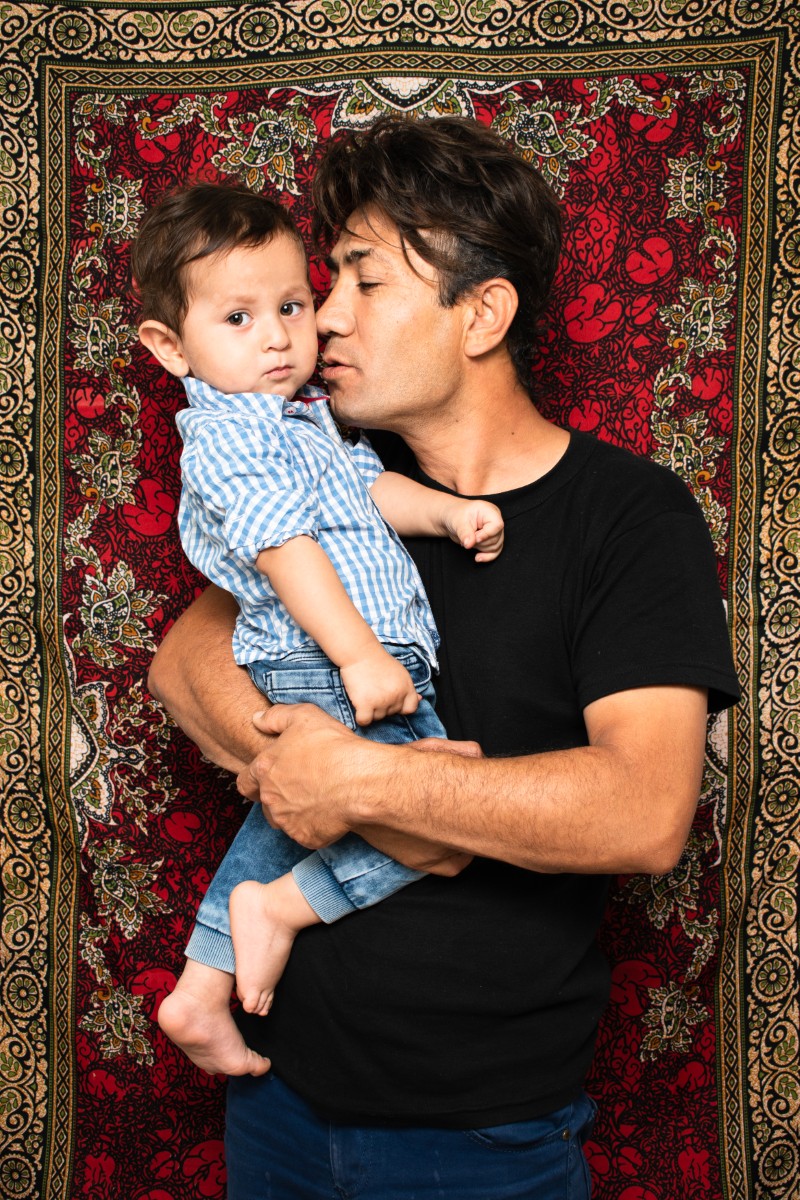

Roholah Mohamadi from Iran. Photographed and interviewed by Asif & Shawiz Tamimi / Witness Change for OSF“I hope they live in a secure world,” says Roholah Mohamadi (35), speaking about his children’s future. Roholah grew up in Iran, but an issue with residence cards meant he and his wife were deported to Afghanistan, his country of birth – a place they neither knew nor felt secure in. “People who lived there didn’t care about bombs or seeing someone being killed… We found it hard to live in this situation.” In Europe, he hoped to find peace and a future for his family. The journey, he says, was “like a movie.” He and his young family were forced to cross a freezing lake, stuffed into an over-crowded, airless bus and had to make a dangerous sea crossing. He thought they’d drown: “When the boat was full of water, I couldn’t even talk to my family. We were crying… My wife couldn’t swim and I wasn’t able to choose which one of them to rescue.” Now they stay in a refugee camp in Greece which is like “a prison.” But, “I try to think positively,” he says. “If we get depressed, no one can give hope to our children.”

But she is proud of herself for the accomplishments that I have achieved and for those I will achieve.

In New York City, challenges remain; she still faces violence, she says.

Nevertheless, she strives to move forward and take life day by day.

“My dream is to get my status and get the house with my girlfriend,” says Leticia (63), a Ugandan asylum seeker living in the United Kingdom. Leticia fled Uganda after her husband found her being intimate with another woman. “The people came, start beating, beating. I ran away,” she said. “It didn’t feel good. And you can’t even go back in his house. He can even kill you.” Leticia now stays with a friend, goes to church and attends an LGBTQI+ group. “Joining the groups make us so strong,” she says. Her children are still in Uganda. She misses them. When things get really difficult, she calls her girlfriend. “We console each other,” she says. She wants people to know that “those people who do not like a gay people, they have to take us as we are.” As for life now in the UK, she says: “With my girlfriend, holding each other… you can kiss on the street, which you can’t do back home.” She says being in the UK is better. Here, she says: “I feel free.”

Roholah Mohamadi from Iran.

In Europe, he hoped to find peace and a future for his family.

The journey, he says, was like a movie.

Mirqedir Mirzat, an Uyghur from East Turkistan. Photographed and interviewed by Mirza Durakovic / Witness Change for OSF“For me today, there is only one dream, either it’s independence or death,” says Mirqedir Mirzat (32). A Uyghur from East Turkistan (called Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in China) now living in France, he began fighting for Uyghur rights when his mother was taken to a re-education camp: “When my mother was locked up… that day changed me – my vision of life.” He joined the French Uyghur’s Association in 2019 as Vice-President, and was also elected as the Deputy Prime Minister for the East Turkistan Government in Exile. Mirzat has not returned home since 2015 and though he misses his parents, “if one day I go back to China, it means I accept their colonization of my country. I will not accept that.” He says what brings him joy is “my family. They are here, fortunately, in a country that respects human rights, a country of freedom.” He says of his homeland: “What leaks out is just 1% of the truth so we can’t imagine what’s going on… Our hearts can’t bear it anymore.”

Now they stay in a refugee camp in Greece which is like a prison.

But, I make a run at think positively, he says.

If we get depressed, no one can give hope to our children.

Iva from Ukraine. Photographed & interviewed by Iva Sidash/Witness Change for The Joseph Handleman I Believe in You Foundation“One of my biggest dream was to move to New York and make career as a musician,” says Iva (21), a student in New York City. “When I moved here, I didn’t expect it to come true. So, right now, I’m just dreaming about being happy.” Iva left Ukraine in 2021 with her family when her mother married an American. Adjusting to life in the US was difficult at first: the language barrier was a “huge deal” and she experienced a sense of “post-move depression.” When the war in Ukraine started, a few months after she arrived in New York, Iva felt isolated and angry: “Since the war started, I’m trying to live as happy as I can, but I never can be happy.” Currently, Iva is studying music performance and plays in volunteer orchestras around the city. “I want to kind of push Ukrainian musical culture here,” she says. She hopes to become a teacher, bringing “American influence, mixed up with Ukrainian traditions, when I come back.” Ultimately, she dreams of “being able to come back home whenever I want.”

How did Witness Change go about finding participants for the project?

For any project, we always work with local organizations/activists/service providers.

Through those connections, we are able to reach different communities in every city where we work.

Roghaia Mohammadi from Afghanistan. Photographed and interviewed by Zahra Gardi / Witness Change for OSFWhen Roghaia Mohammadi (34) left her home in Afghanistan and then Iran, her dream was to “experience a peaceful, war-free life and get ahead by working hard and studying.” In pursuit of this dream, the mother of three has endured robbery, deportation, violence against her children, and separation from one of her sons. The most difficult part of her journey was in a smuggler’s car. She recalls: “My son panicked and couldn’t breathe. I begged the driver to stop… he told me he did not care if my son died, and that if he died, we would throw him out of the vehicle. I just cried and fanned my son with a piece of a cardboard box.” Now, as she seeks asylum in Greece, her thoughts are elsewhere: “Most nights before bed or when I am alone, I think about my second son in Iran. I am physically here, but my soul was left in Iran.” Still, she finds hope: “Thinking about a better future for myself and my family helps me. I have always been a strong person, but this trip has made me even stronger.”

Leticia fled Uganda after her husband found her being intimate with another woman.

The people came, start beating, beating.

I ran away, she said.

Nilofar Said Por from Afghanistan. Photographed and interviewed by Ayat/Witness Change for The Joseph Handleman I Believe in You Foundation“Because our future is in our own hands, we can study and if my husband’s work permit comes…we can go to the house and schools we dream of, we can take our children there and provide them a good life.” Nilofar Said Por, 29, sought asylum in New York with her family after fleeing Afghanistan in 2023. “We did not imagine that our country would be taken over by the Taliban all of a sudden and we would have to leave…because our lives were in danger.” The journey to the U.S. was difficult, not knowing the language and going for days without eating when shelters couldn’t provide halal food. “We went through a lot of hard days and were depressed and stressed,” she says, “but I had hope that I came here and that the lives of our children and ourselves would be better.” Nilofar misses her family back home but she’s hopeful about the future: “My dream is…that I can continue my studies or work in the field of law that I graduated from. If it doesn’t work, I want to work in midwifery or nursing.”

It didn’t feel good.

And you could’t even go back in his house.

He can even kill you.

Adonis from Senegal. Photographed & interviewed by Abdoulaye Ndoye/Witness Change for The Joseph Handleman I Believe in You Foundation.“It was my dream actually to stay in my country,” recounts Adonis (pseud, 30), a Senegalese refugee now living overseas. Before leaving, he dreamt of “staying in my country, contributing, giving the best of myself, the best of my country, and finishing my studies.” However, “where I come from, it’s very different to want to stand up for something… There are not the same visions and the same realities and therefore it is not easy.” Settling into a new life has its challenges. These days, Adonis says, he isn’t happy, but he is getting by: “I have a hard time sometimes when I think my life has turned out that way. Sometimes you are confronted with things that you did not choose.” His strength is patience and the ability to “manage the present moment… and to aspire to the future.” Now, he says, “My dream is the present. It is today.” Life, he says, “is beautiful and meant to live.”

Leticia now stays with a friend, goes to church and attends an LGBTQI+ group.

Joining the groups make us so strong, she says.

Her children are still in Uganda.

When things get really difficult, she calls her girlfriend.

We console each other, she says.

She says being in the UK is better.

Here, she says: I feel free.

Many participants kept their faces hidden, while others were okay facing the camera.

What discussions went on with the participants about how they wanted to appear?

Its extremely important that the people being photographed know how and where their picture/story will be used.

Its extremely important that we are always working in a way that is safe and respectful.

Mirqedir Mirzat, an Uyghur from East Turkistan.

I will not accept that.

He says what brings him joy is my family.

They are here, fortunately, in a country that respects human rights, a country of freedom.

Was there any theme that you felt was recurring in the stories they told?

The themes of the project are emotional strengths, emotional challenges, and dreams of the future.

Every story touches on these themes.

When I moved here, I didn’t expect it to come true.

So, right now, I’m just dreaming about being happy.

Iva left Ukraine in 2021 with her family when her mother married an American.

Currently, Iva is studying music performance and plays in volunteer orchestras around the city.

I want to kind of push Ukrainian musical culture here, she says.

Ultimately, she dreams of being able to come back home whenever I want.

What do you think the public would be most surprised to learn about these refugees?

I think host populations tend to look at refugees as completely different from them.

Its a bit cliche, but what they can learn is how similar we all are.

Roghaia Mohammadi from Afghanistan.

The most difficult part of her journey was in a smugglers car.

She recalls: My son panicked and couldn’t breathe.

I just cried and fanned my son with a piece of a cardboard box.

I am physically here, but my soul was left in Iran.

Still, she finds hope: Thinking about a better future for myself and my family helps me.

I have always been a strong person, but this trip has made me even stronger.

How does Witness Change view its role in creating discourse around marginalized communities?

We give a shot to ensure that the voices of marginalized communities are always centered in our work.

By working with local partners and advocating through the press and exhibitions, we feel we can accomplish this.

Nilofar Said Por from Afghanistan.

Nilofar Said Por, 29, sought asylum in New York with her family after fleeing Afghanistan in 2023.

If it doesnt work, I want to work in midwifery or nursing.

What do you hope people take away from1000 Dreams?

However, where I come from, it’s very different to want to stand up for something…

There are not the same visions and the same realities and therefore it is not easy.

Settling into a new life has its challenges.

Sometimes you are confronted with things that you did not choose.

His strength is patience and the ability to manage the present moment… and to aspire to the future.

Now, he says, My dream is the present.

Life, he says, is beautiful and meant to live.

The hope is that we can reach more people and create deeper engagement this way.

But we are always looking for new connections and new impacts.

1000 Dreams Project:Website|InstagramWitness Change:Website|Facebook|Instagram