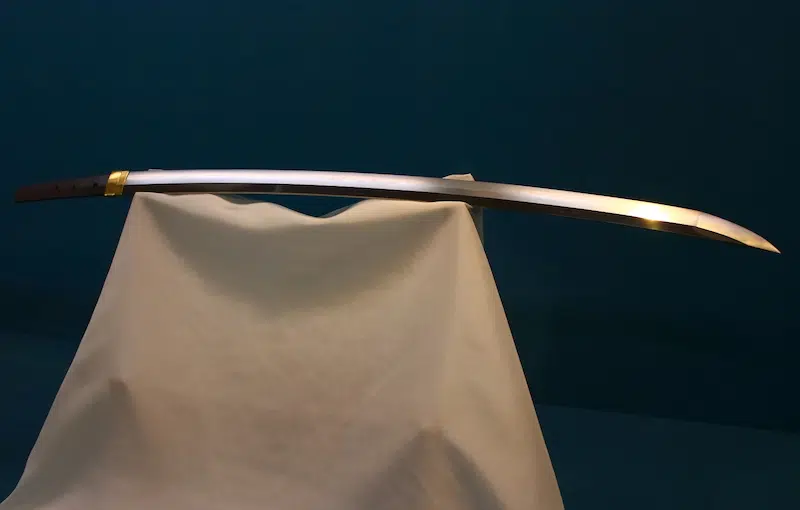

One such artform is swordsmithing, a tedious process in which swords such as the legendarykatanaare made.

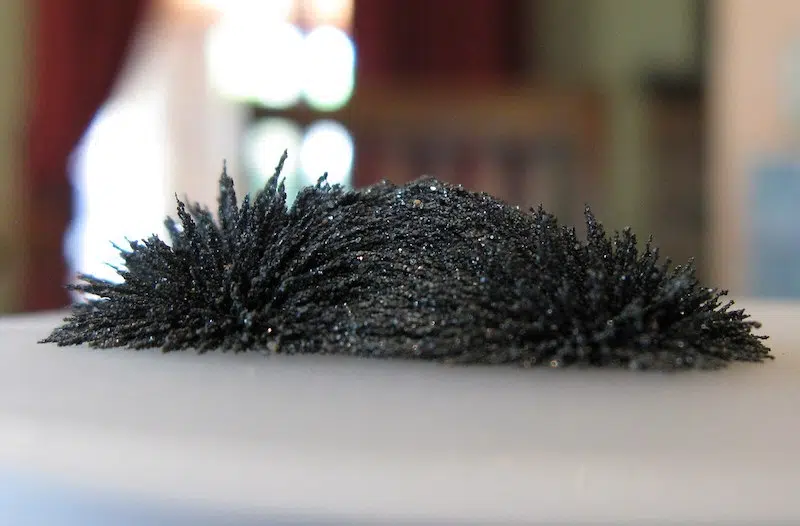

What renders their construction so labor-intensive is that these swords are, perhaps counterintuitively, composed of sand.

This smelting phase can last for days, requiring supervision without any interruptions.

A Japanese katana. (Photo: Kakidai, viaWikimedia Commons,CC 4.0)

Once the smelting process is complete, the besttamahaganepieces are selected from thetatara.

The folding also produces the patterns, orjihada, for whichkatanablades are known.

Preparing the swords edge is often considered the most important yet challenging aspect of swordsmithing.

Iron sand from Four Peaks mountain near Phoenix, Arizona, attracted to a magnet. (Photo: Jlahorn, viaWikimedia Commons,CC 3.0)

Here, the swordsmith carefully heats the blade.

As the temperature rises, crystal structures within the metal begin to change.

Finally, blades are then polished using water stones, generating a finer and sharper finish.

Katana mountings decorated with maki-e lacquer in the 1800s. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, viaWikimedia Commons,CC0 1.0)

For centuries, Japanese swordsmiths have transformed iron sand into katanas.

Iron sand from Four Peaks mountain near Phoenix, Arizona, attracted to a magnet.

Katana mountings decorated with maki-e lacquer in the 1800s.

Japanese sword blade and sharpening stone and water bucket at 2008 Cherry Blossom Festival, Seattle Center, Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Joe Mabel, viaWikimedia Commons,GNU Free Documentation License)

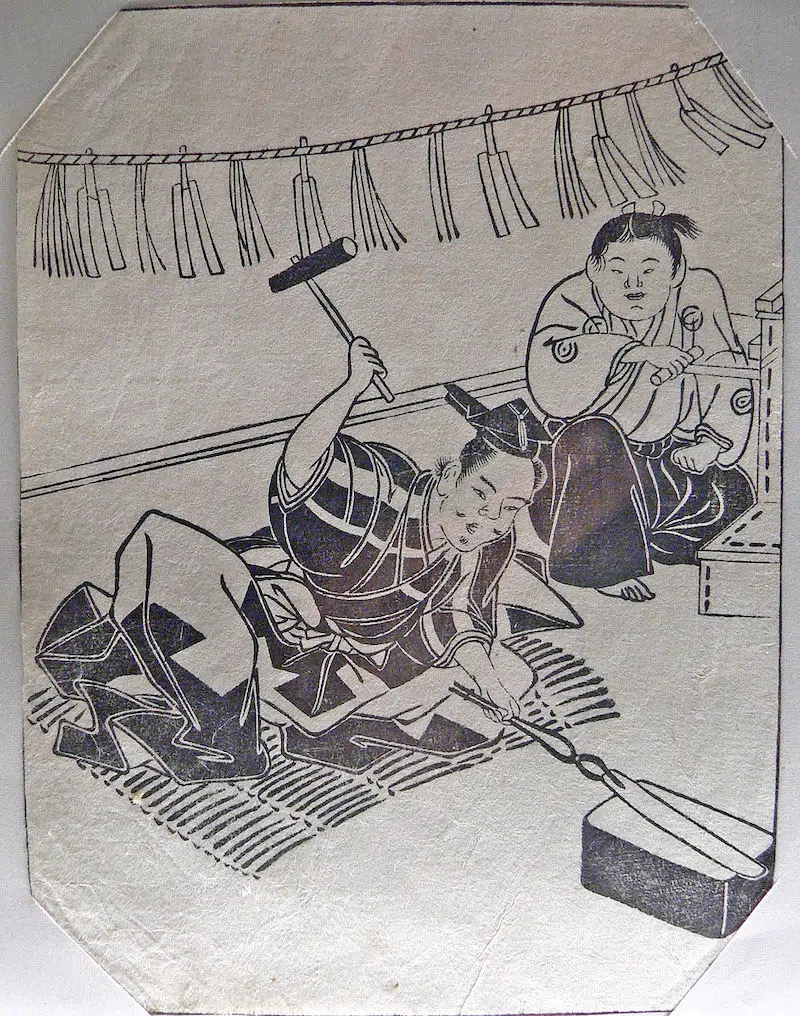

Blacksmith scene, print from a Edo period book.

Blacksmith scene, print from a Edo period book. (Photo: Rama, viaWikimedia Commons,CC 2.0)