If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission.

kindly readour disclosurefor more info.

Curtis was on the move for more than three decades, living among dozens of tribes.

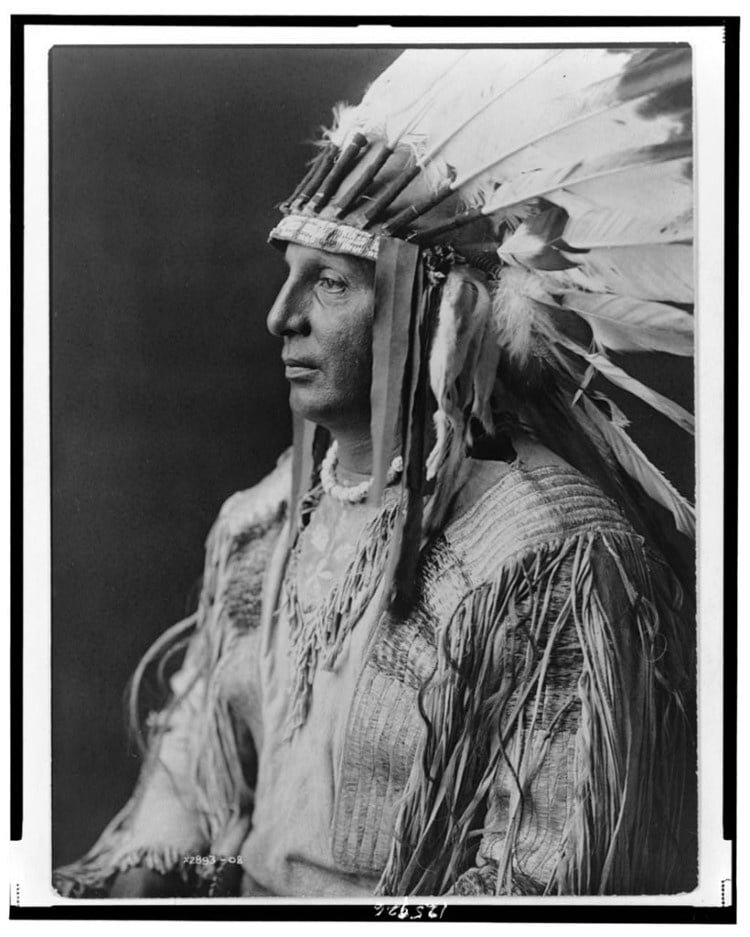

White Shield – Arikara, 1908 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaLibrary of Congress, Public domain)This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please readour disclosurefor more info.

Interested in more than just photography, Curtis wished to capture a full view of Native American culture.

Less than half of the projected 500 sets were printed and scholars were skeptical of Curtis' observation skills.

His images were posed, and he often paid people to perform in staged scenes or dances.

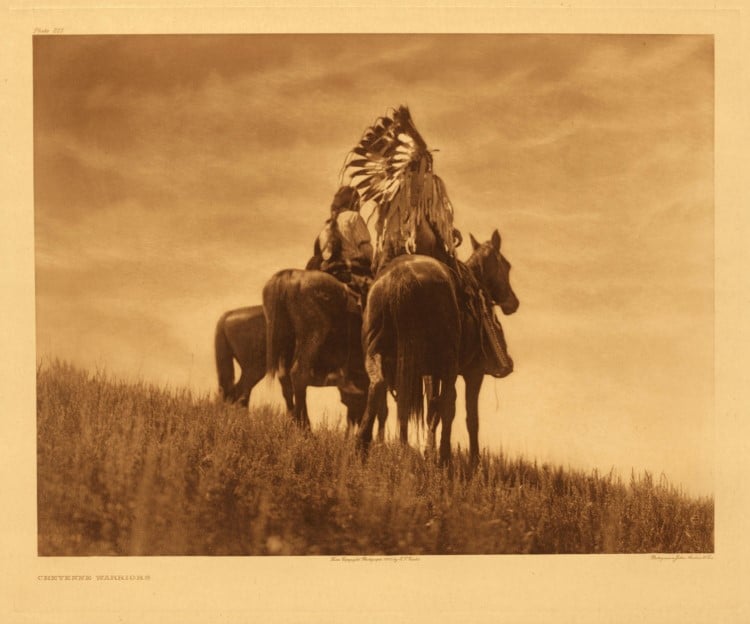

Cheyenne Warriors, 1905 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

While Curtis' imagery is a romanticized view of these indigenous populations, it is still valuable.

He sought to observe and understand by going directly into the field.

This includes folklore, clothing, traditional foods, housing, leisure activities, and ceremonies such as funerals.

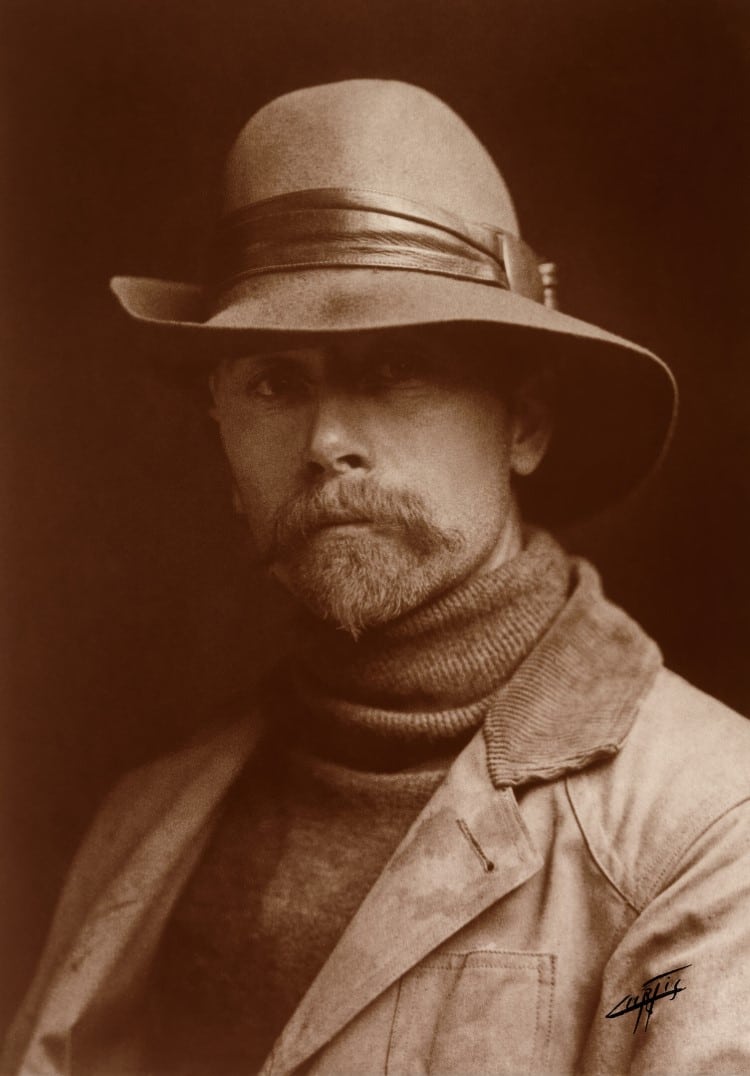

Self-portrait, 1899. (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaWikimedia Commons, Public domain)

It’s estimated that today, production of the volumes would costmore than $35 million dollars.

Incredibly, we can still view his work today.

This is all the more amazing when one considers that Curtis destroyed all of his glass plate negatives.

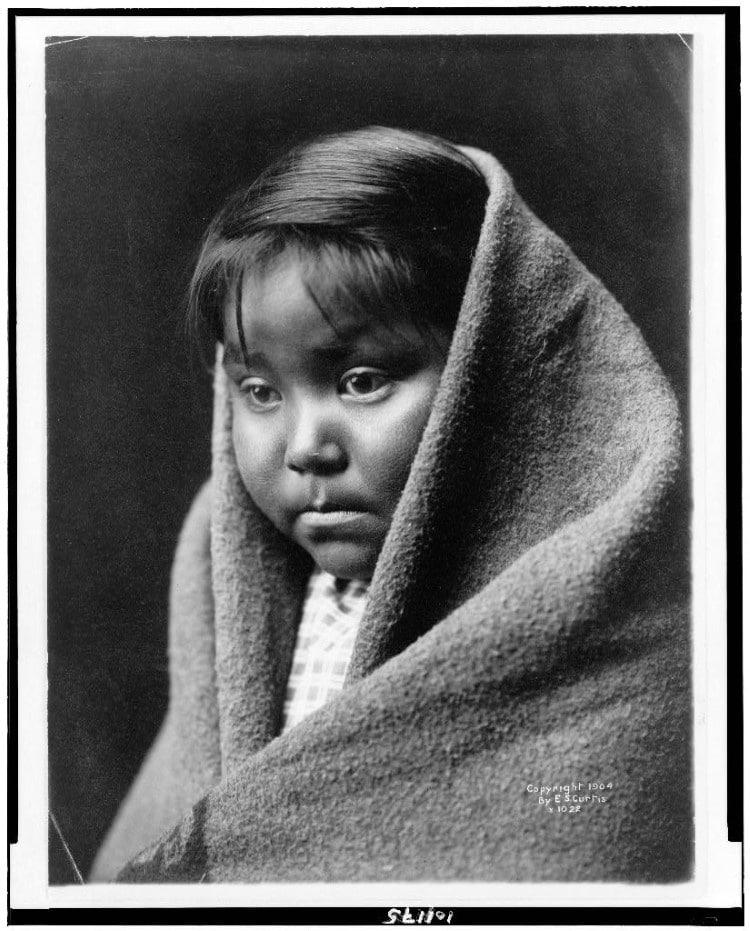

Navajo child, 1904 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaLibrary of Congress, Public domain)

There are many ways to still see Curtis’s work.

In 2004, Northwestern UniversitydigitizedThe North American Indianand placed it online.

Born in 1868, photographer Edward S. Curtis spent over 30 years documenting Native American culture.

Óla – Noatak, 1928 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaLibrary of Congress, Public domain)

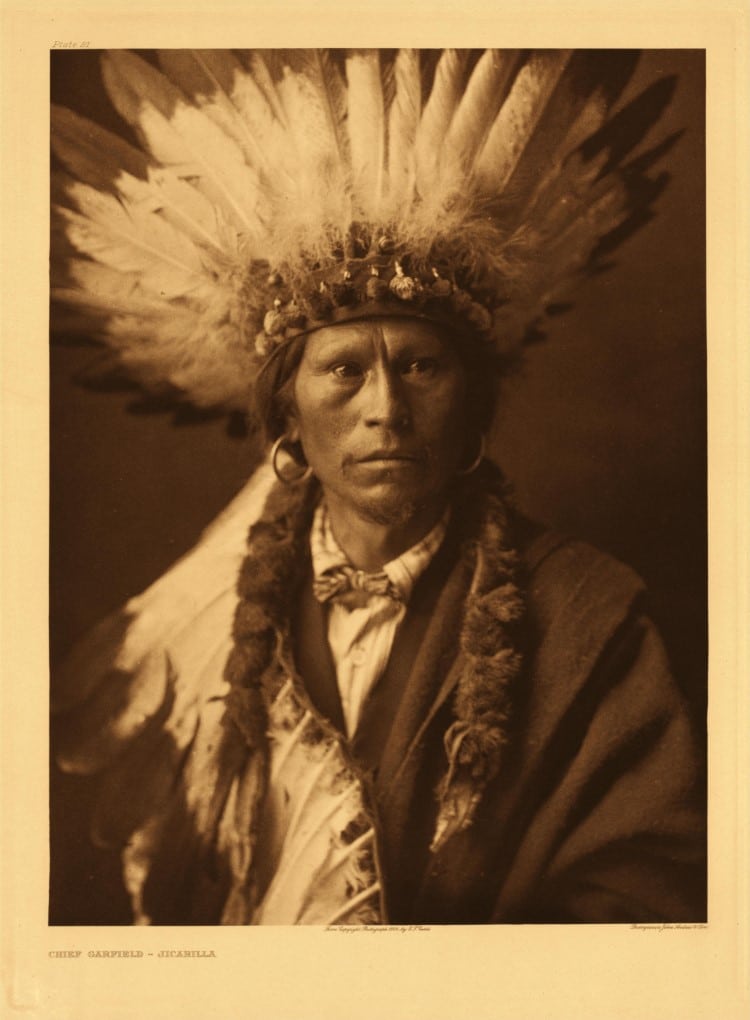

Chief Garfield – Jicarilla, 1904 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

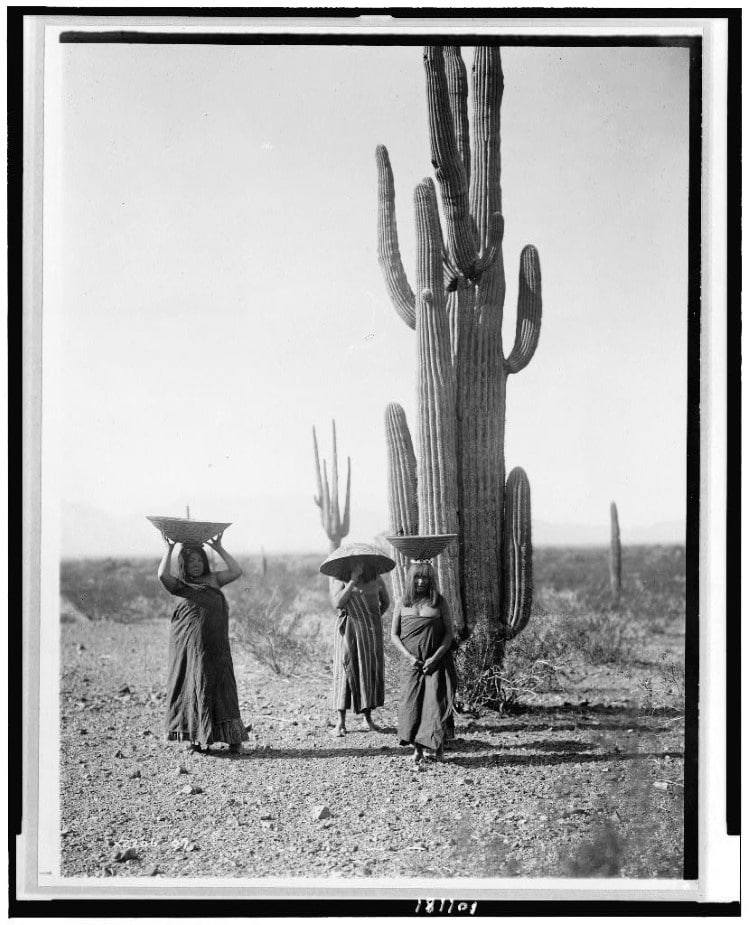

Maricopa women gathering fruit from Saguaro cacti, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaLibrary of Congress, Public domain)

Apache man, 1903 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaLibrary of Congress, Public domain)

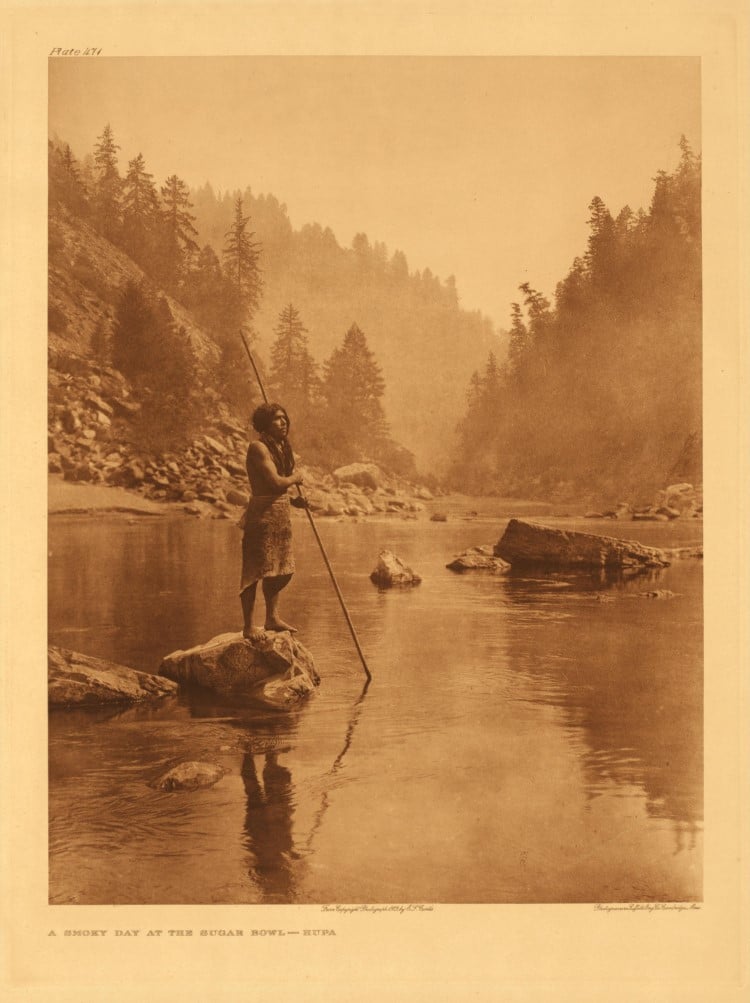

A Smoky Day at the Sugar Bowl – Hupa, 1923 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

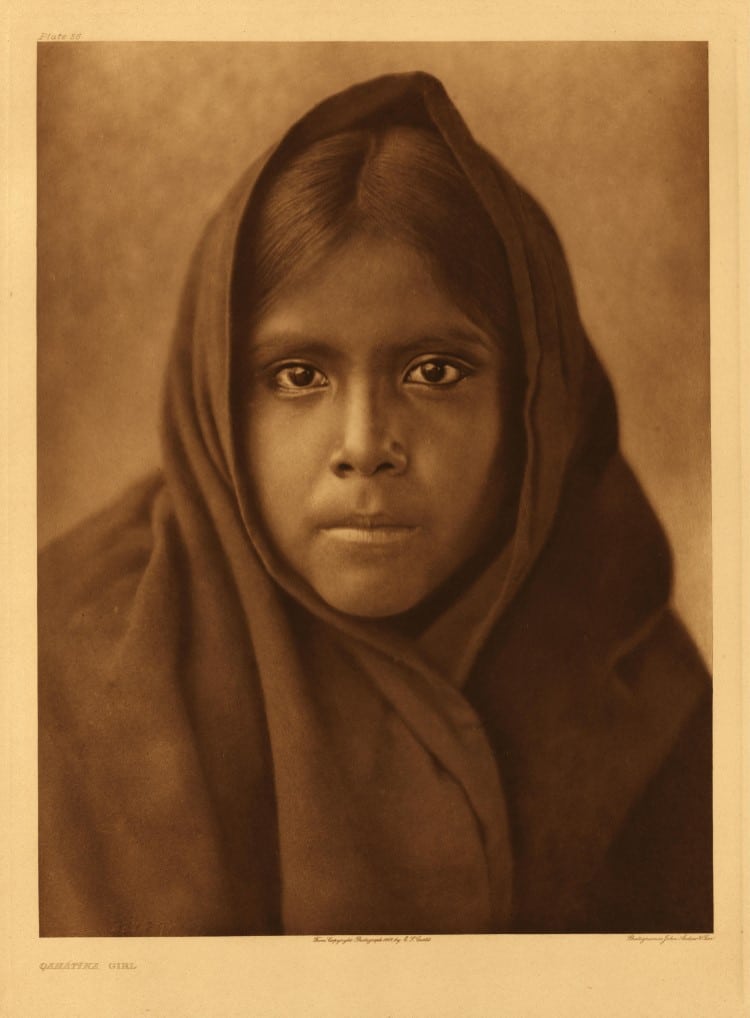

Qahátīka Girl, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

Blackfoot Finery, 1926 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

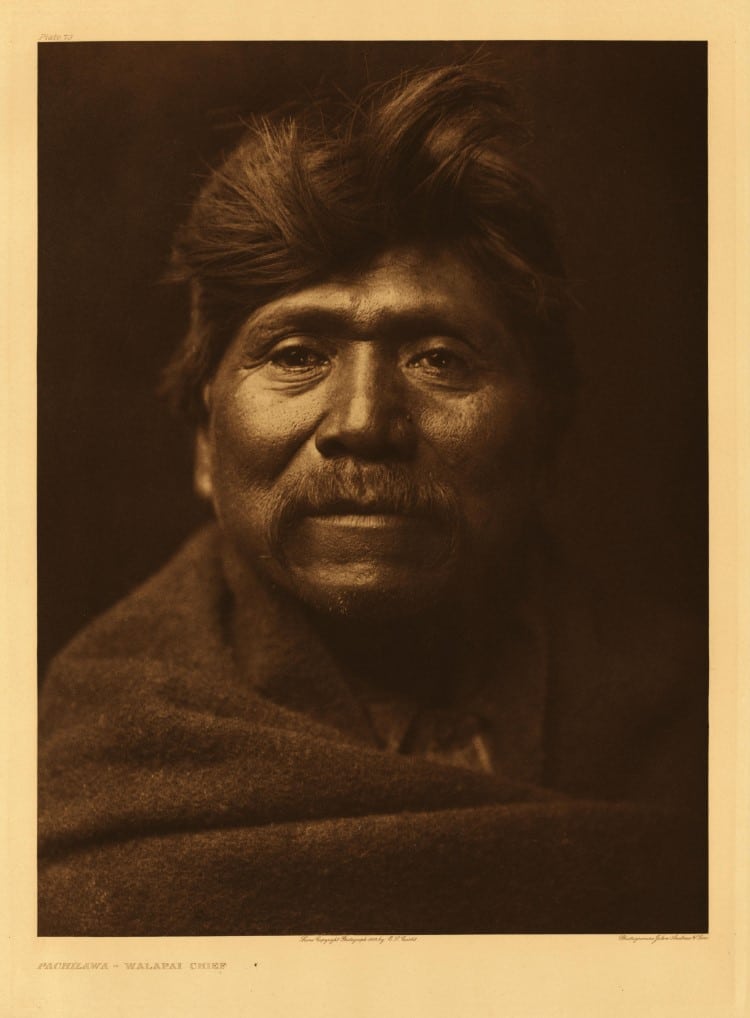

Pakílawa – Walapai Chief, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)

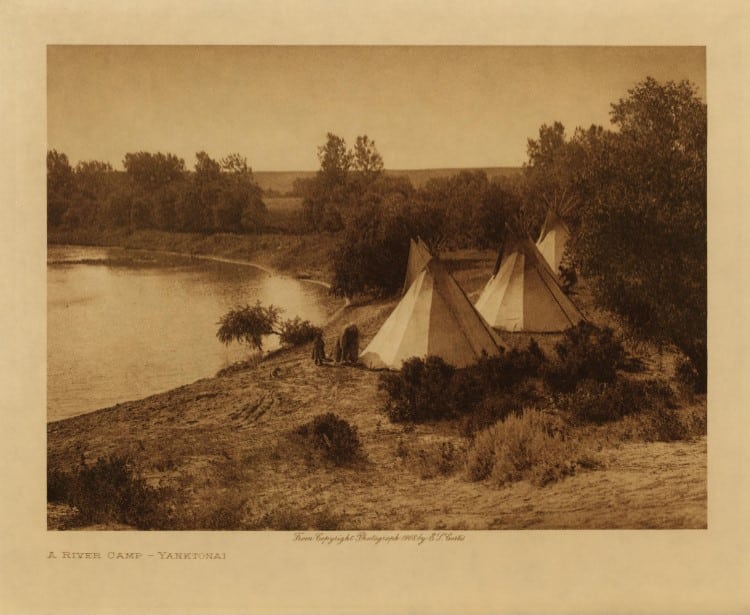

Yanktonai River Camp, 1908 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis viaNorthwestern University, Public domain)