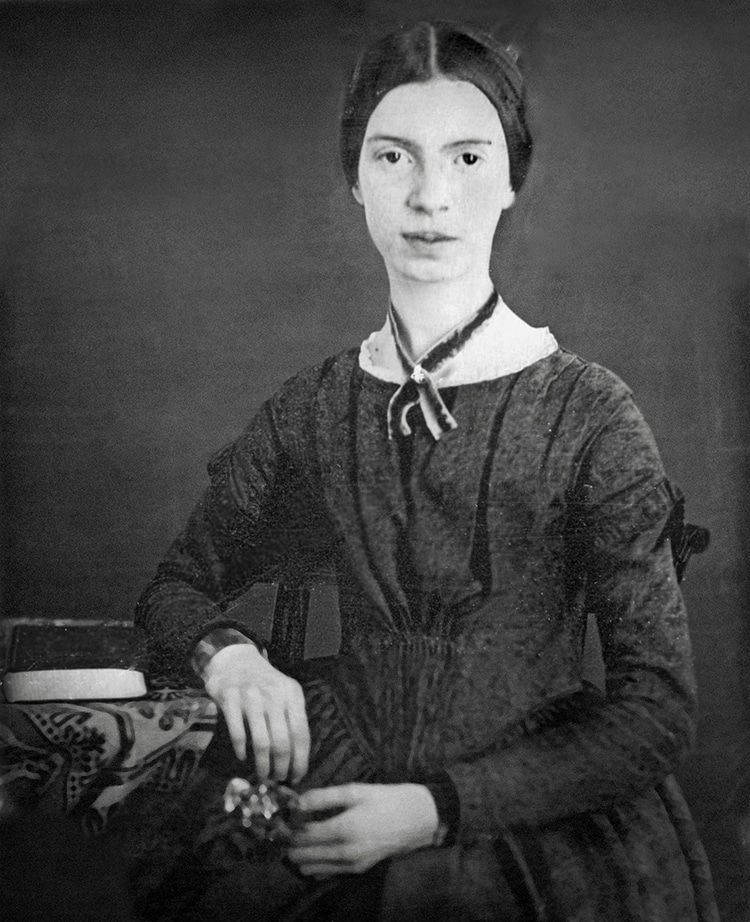

Digitally restored black and white daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847.

(Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)This post may contain affiliate links.

If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission.

Digitally restored black and white daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please readour disclosurefor more info.

just readour disclosurefor more info.

The now-renownedEmily Dickinsonis widely regarded as one of the most important poets of American literature.

Famously a recluse in her later years, the overwhelmingmajority of her poemswere never published until after her death.

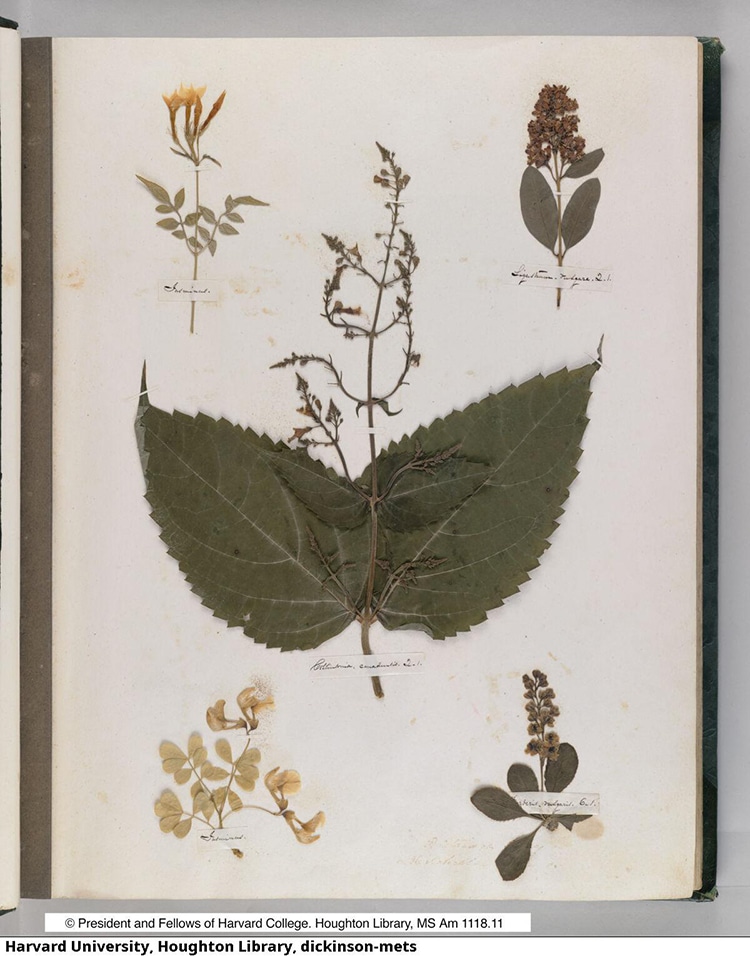

First page of Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. (Photo:Houghton Library, Harvard University, Public domain)

Poetry wasn’t her only passion, though.

From a young age, she studied botany.

While still a student, the avid anthophile compiled a remarkable herbarium, a compilation of dried plants.

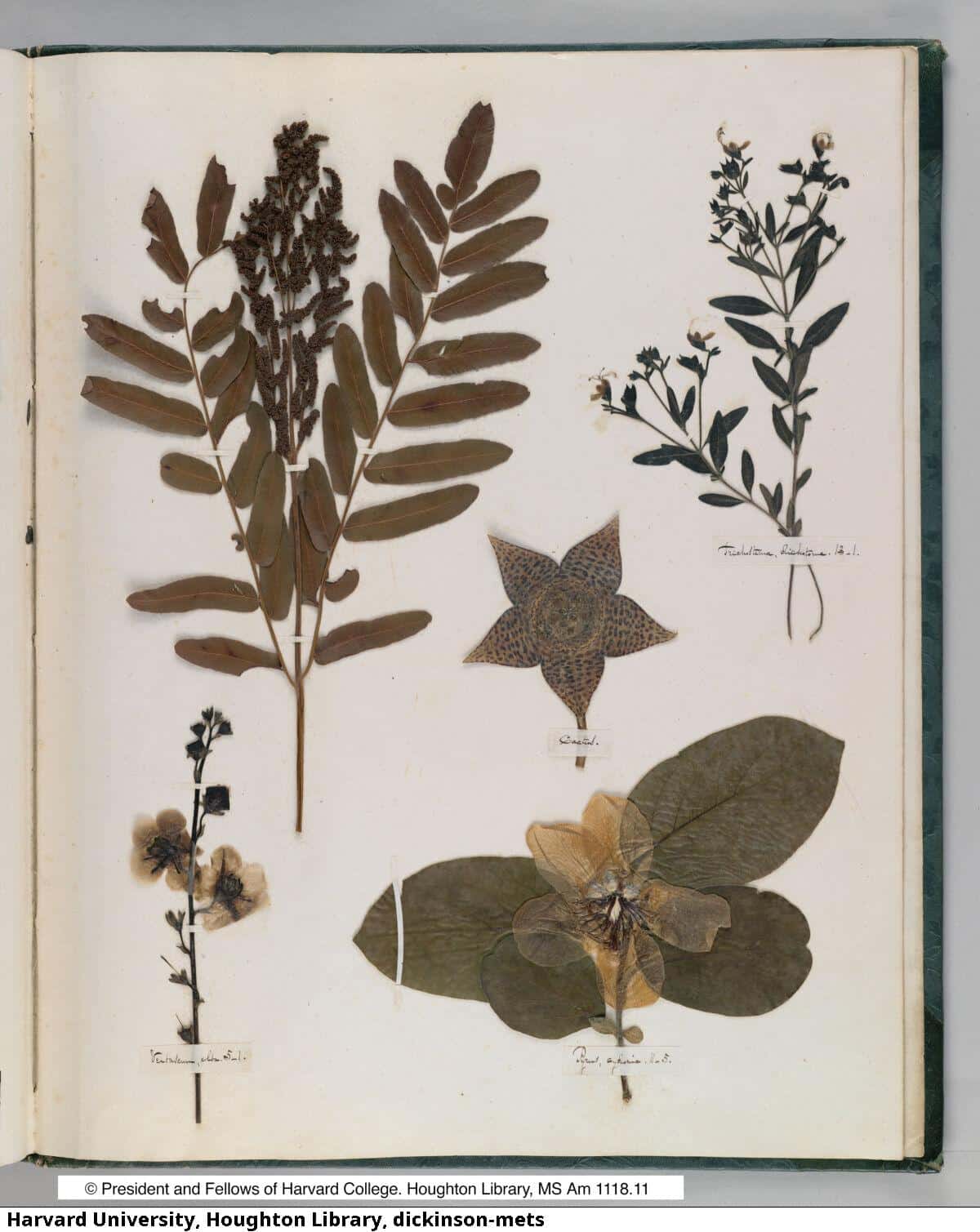

Photo:Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)

Luckily, the Houghton Library used digital photography to make thecollectionviewable to scholars, and the general public.

Dickinson’s neat handwriting can be viewed via the labels that use the scientific name of the plants.

Farr argues that one can only understand Emily Dickinson the poet if one understands Emily Dickinson the gardener.

Photo:Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)

Yet the collection opens with jasmine, a far more exotic species.

First page of Emily Dickinson’s herbarium.

Photo:, Harvard University (Public domain)

Photo:, Harvard University (Public domain)

Photo:Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)