That was the last anyone would see of them for 14 months.

And yet, against all odds, Alvarenga had done the impossiblehe had survived.

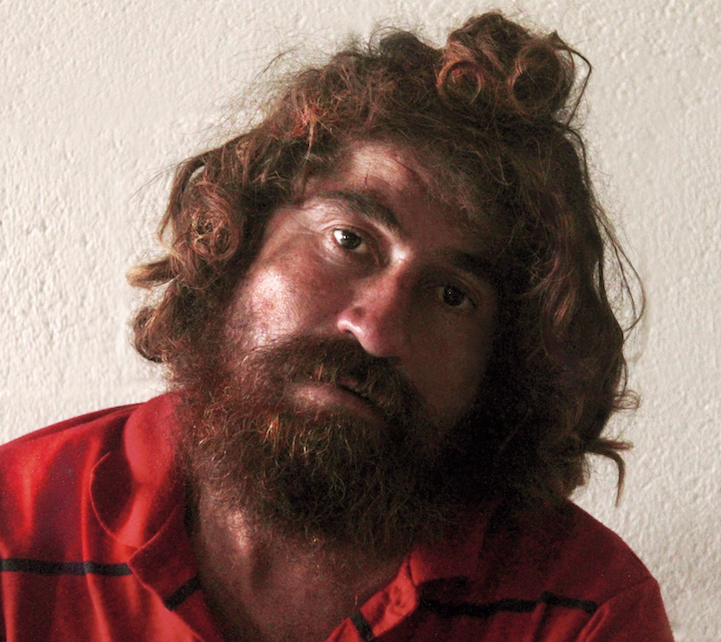

There was no hiding the fact that this man had been at sea for a considerable time.

His hair was matted upwards like a shrub.

His beard curled out in wild disarray.

His ankles were swollen, his wrists tiny; he could barely walk.

He refused to make eye contact and often hid his face.

He was 6,700 miles from the place he had set out from.

He had drifted for 438 days.

Days later, Alvarenga faced the world’s press.

Expecting a gaunt and bedridden victim, a ripple of disbelief went through the crowd.

Alvarenga cracked a quick smile and waved to the cameras.

Several observers noted a similarity to the Tom Hanks character in the movie Cast Away.

The photo of the bearded fisherman shuffling ashore went viral.

Briefly, Alvarenga became a household name.

Who survives 14 months at sea?

Only a Hollywood screenwriter could write a tale in which such a journey ends happily.

I was sceptical, but as a Guardian reporter in the region, I began to investigate.

Over the course of more than 40 interviews, he described his extraordinary survival at sea.

This is his story.

He was a veteran captain and knew that he needed to regain the initiative.

With no raised structure, no glass and no running lights, it was virtually invisible at sea.

If they could bring it ashore, they would have enough money to survive for a week.

The icebox in which Alvarenga hid from the sun.

But at the last minute, Perez couldn’t join him.

Alvarenga and Crdoba had never spoken before, much less worked together.

As the weather worsened, Crdoba’s resolve disintegrated.

At times he refused to bale and instead held the rail with both hands, vomiting and crying.

He had signed up to make $50.

He was capable of working 12 hours straight without complaining and was athletic and strong.

But this crashing, soaking journey back to shore?

He was sure their tiny craft would shatter and sharks would devour them.

He began to scream.

Around 9am, Alvarenga spotted the rise of a mountain on the horizon.

They were approximately two hours from land when the motor started coughing and spluttering.

He pulled out his radio and called his boss.

The motor is ruined!

We have no GPS, it’s not functioning.

Lay an anchor, Willy ordered.

We have no anchor, Alvarenga said.

OK, we are coming to get you, Willy responded.

Come now, I am really getting fucked out here, Alvarenga shouted.

These were his final words to shore.

As the waves thumped the boat, Alvarenga and Crdoba began working as a team.

Each man would brace and lean against a side of the open-hulled boat to counteract the roll.

Their beach sandals provided no traction on the deck.

One by one they hauled them out of the cooler, swinging the carcasses into the ocean.

Falling overboard was now more dangerous than ever: the bloody fish were sure to attract sharks.

Next they tossed the ice and extra gasoline.

But at around 10am the radio died.

It was before noon on day one of a storm that Alvarenga knew was likely to last five days.

Losing the GPS had been an inconvenience.

The failed motor was a disaster.

Now, without radio contact, they were on their own.

The storm roiled the men all afternoon as they fought to bale water out of the boat.

They were both ready to faint with exhaustion, but Alvarenga was also furious.

He picked up a heavy club normally used to kill fish and began to bash the broken engine.

Then he grabbed the radio and GPS unit and angrily threw the machines into the water.

The sun sank and the storm churned as Crdoba and Alvarenga succumbed to the cold.

They turned the refrigerator-sized icebox upside down and huddled inside.

Progress was slow but the pond at their feet gradually grew smaller.

Darkness shrank their world, as a gale-force wind ripped offshore and drove the men farther out to sea.

Were they now back to where they had been fishing a day earlier?

Were they heading north towards Acapulco, or south towards Panama?

With only the stars as guides, they had lost their usual means of calculating distance.

Without bait or fish hooks, Alvarenga invented a daring strategy to catch fish.

They ate fish after fish.

Alvarenga stuffed raw meat and dried meat into his mouth, hardly noticing or caring about the difference.

Within days, Alvarenga began to drink his urine and encouraged Crdoba to follow suit.

Alvarenga had long ago learned the dangers of drinking seawater.

Despite their longing for liquid, they resisted swallowing even a cupful of the endless saltwater that surrounded them.

He began to grab jellyfish from the water, scooping them up in his hands and swallowing them whole.

It burned the top part of my throat, but wasn’t so bad.

The rhythm of raindrops on the roof was unmistakable.

Piata, Alvarenga screamed as he slipped out.

His crewmate awoke and joined him.

Crdoba scrubbed a grey five-gallon bucket clean and positioned its mouth skyward.

Within an hour, the bucket had an inch, then two inches of water.

The men laughed and drank every couple of minutes.

After their initial attack on the water supplies, however, they vowed to maintain strict rations.

They grabbed and stored every empty water bottle they found.

It was the first fresh food the two men had seen for a long time.

They treated the soggy carrots with reverence.

We would talk about our mothers, Alvarenga recalled.

And how badly we had behaved.

We asked God to forgive us for being such bad sons.

We imagined if we could hug them, give them a kiss.

We promised to work harder so they would not have to work any more.

But it was too late.

They were on the same boat but headed on different paths.

Alvarenga offered tiny chunks of bird meat, occasionally a bite of turtle.

Crdoba clenched his mouth.

Depression was shutting his body down.

The two men made a pact.

If Crdoba survived, he would travel to El Salvador and visit Alvarenga’s mother and father.

I am dying, I am dying, I am almost gone, Crdoba said one morning.

Don’t think about that.

Let’s take a nap, Alvarenga replied as he lay alongside Crdoba.

I am tired, I want water, Crdoba moaned.

His breath was rough.

Alvarenga retrieved the water bottle and put it to Crdoba’s mouth, but he did not swallow.

Instead he stretched out.

His body shook in short convulsions.

He groaned and his body tensed up.

He screamed into Crdoba’s face, Don’t leave me alone!

You have to fight for life!

What am I going to do here alone?

Crdoba didn’t reply.

Moments later he died with his eyes open.

I propped him up to keep him out of the water.

I was afraid a wave might wash him out of the boat, Alvarenga told me.

I cried for hours.

The next morning he stared at Crdoba in the bow of the boat.

He asked the corpse, How do you feel?

How was your sleep?

I slept good, and you?

Have you had breakfast?

Alvarenga answered his own questions aloud, as if he were Crdoba speaking from the afterlife.

The easiest way to deal with losing his only companion was simply to pretend he hadn’t died.

First I washed his feet.

His clothes were useful, so I stripped off a pair of shorts and a sweatshirt.

I put that on it was red, with little skull-and-crossbones and then I dumped him in.

And as I slid him into the water, I fainted.

When he awoke just minutes later, Alvarenga was terrified.

What could I do alone?

Without anyone to speak with?

Why had he died and not me?

I had invited him to fish.

I blamed myself for his death.

With his eyesight fine-tuned, Alvarenga could now identify a tiny speck on the horizon as a ship.

Every sighting pumped Alvarenga with an energy boost that jolted him to wave, jump and flail for hours.

About 20 separate container boats paraded across the horizon, yet the maddening ship-tease still excited him.

Alvarenga let his imagination run wild so you can keep sane.

He was mastering the art of turning his solitude into a Fantasia-like world.

He started his mornings with a long walk.

I would stroll back and forth on the boat and imagine that I was wandering the world.

By doing this I could make myself believe that I was actually doing something.

Not just sitting there, thinking about dying.

With this lively entourage of family, friends and lovers, Alvarenga insulated himself from bleak reality.

He was convinced his next destination was heaven.

He was whizzing along on a smooth current, when suddenly the sky filled with shore birds.

The muscles in his neck tightened.

A tropical island emerged from the mist.

A green Pacific atoll, a small hill surrounded by a kaleidoscope of turquoise waters.

Hallucinations didn’t last this long.

Had his prayers finally been answered?

Alvarenga’s racing mind imagined multiple disaster scenarios.

He could blow off course.

He could drift backward it had happened before.

He stared at the land as he tried to pick out details from the shore.

It was a tiny island, no bigger than a football field, he calculated.

It looked wild, without roads, cars or homes.

With his knife, he cut away the ragged line of buoys.

It was a drastic move.

But Alvarenga could see the shoreline clearly and he gambled that speed was of greater importance than stability.

In an hour he had drifted near the island’s beach.

As the wave pulled away, Alvarenga was left face down in the sand.

I held a handful of sand like it was a treasure, he later told me.

Making radio contact after landing on Ebon Atoll.

He was unable to stand for more than a few seconds.

I was totally destroyed and as skinny as a board, he said.

The only thing left was my intestines and gut, plus skin and bones.

My arms had no meat.

My thighs were skinny and ugly.

He looks weak and hungry.

My first thought was, this person swam here, he must have fallen off a ship.

After tentatively approaching each other, Emi and Russel welcomed him into their home.

Alvarenga drew a boat, a man and the shore.

Then he gave up.

How could he explain a 7,000-mile drift at sea with stick figures?

He asked for medicine.

He asked for a doctor.

The native couple smiled and kindly shook their heads.

Even though we did not understand each other, I began to talk and talk, Alvarenga told me.

The more I talked, the more we all roared with laughter.

I am not sure why they were laughing.

I was laughing at being saved.

Within hours a group, including police and a nurse, had come to rescue Alvarenga.

They had to persuade him to get on a boat with them back to Ebon.

Reporters in Hawaii, Los Angeles and Australia scrambled to reach the island to interview this alleged castaway.

The single phone line on Ebon became a battleground, as reporters tried to discover tantalising details.

The winds were high, Marroqun said.

We had to stop the search flights after two days because of poor visibility.

I began to investigate, talking to people up and down the coast of Mexico.

I spoke with oceanographers and commercial fishermen familiar with the area.

Everyone confirmed that Alvarenga’s version of life at sea was in line with what they would expect.

He was out there for a long time, the US ambassador said.

Back home in El Salvador.

For months he was in shock, afraid of the water.

Photo: Oscar Machon

Meanwhile back in the Marshall Islands, Alvarenga’s medical condition steadily worsened.

His feet and legs were swollen.

The doctors suspected the tissues had been deprived of water for so long that they now soaked up everything.

Alvarenga believed the parasites might rise up to his head and attack his brain.

Deep sleep was impossible and he thought often of Crdoba’s death.

It was not the same to be celebrating survival alone.

He sat with her for two hours, answering all her questions.

Life on land has not been straightforward: for months, Alvarenga was still in shock.

He had developed a deep fear of not only the ocean, but even the sight of water.

He slept with the lights on and needed constant company.

For 438 days, he lived on the edge of sanity.

I suffered hunger, thirst and an extreme loneliness, and didn’t take my life, Alvarenga says.

You only get one chance to live so appreciate it.

How did you manage to get in touch with him and convince him to share his story with you?

Jonathan Franklin:I waited approximately six months before my first interview.

There was no way I was going to force my way into his life.

He nicknamed reporters the cockroaches and worked hard to avoid them.

MMM:Seeing Alvarenga in his home in El Salvador, what were your impressions of him?

Was this a man who was clearly, visibly forever changed by his harrowing experience?

JF:He is a happy man, surrounded by friends.

I imagined that he would be haunted by fears and demons, not at all.

He even goes out on small boats with his friends now and then.

MMM:You embarked on your own incredible endeavor by reporting and writing this book438 Days.

In your eyes, what made this a story worth telling?

JF:I have deep faith that each of us carries a formidable reserve of good will and resilience.

Alvarenga had all three in good measure.

MMM:Are you still in touch with Alvarenga?

Can you give an update on how he is doing today?

You’d never guess that he had suffered so much until you sit to listen to him.

He’s an amazing storyteller.

Alvarenga and Franklin on the beach in El Salvador.

Jonathan Franklin:Website|Twitter

My Modern Met granted permission to use text by Jonathan Franklin.

All images courtesy of the author.