Lena and her daughter Christina are standing at the entrance of their chum.

Lenas mother was the first in the family to give birth in a hospital.

It was after this time that air transport for pregnant women to the city hospital was introduced.

Lena and her daughter Christina are standing at the entrance of their chum. Lena’s large belly is obvious under her dress, and there is no doubt that she is nine months pregnant.Since the 1960s, Nenets women have been instructed to leave their tundra homes to give birth in a hospital. Lena’s mother was the first in the family to give birth in a hospital. Lena’s grandmother, Praskovya, gave birth to five children in her tundra home, assisted by elderly women from neighboring chums who were experienced with births and served as midwives. It was after this time that air transport for pregnant women to the city hospital was introduced.

Documentary photographerAlegra Allyhas dedicated her life to telling the stories of indigenous people around the world.

The results of Ally’s two-month stay with the Nentsy paints an incredible picture of adaptation and survival.

As time moves forward, this group adapts without losing its identity.

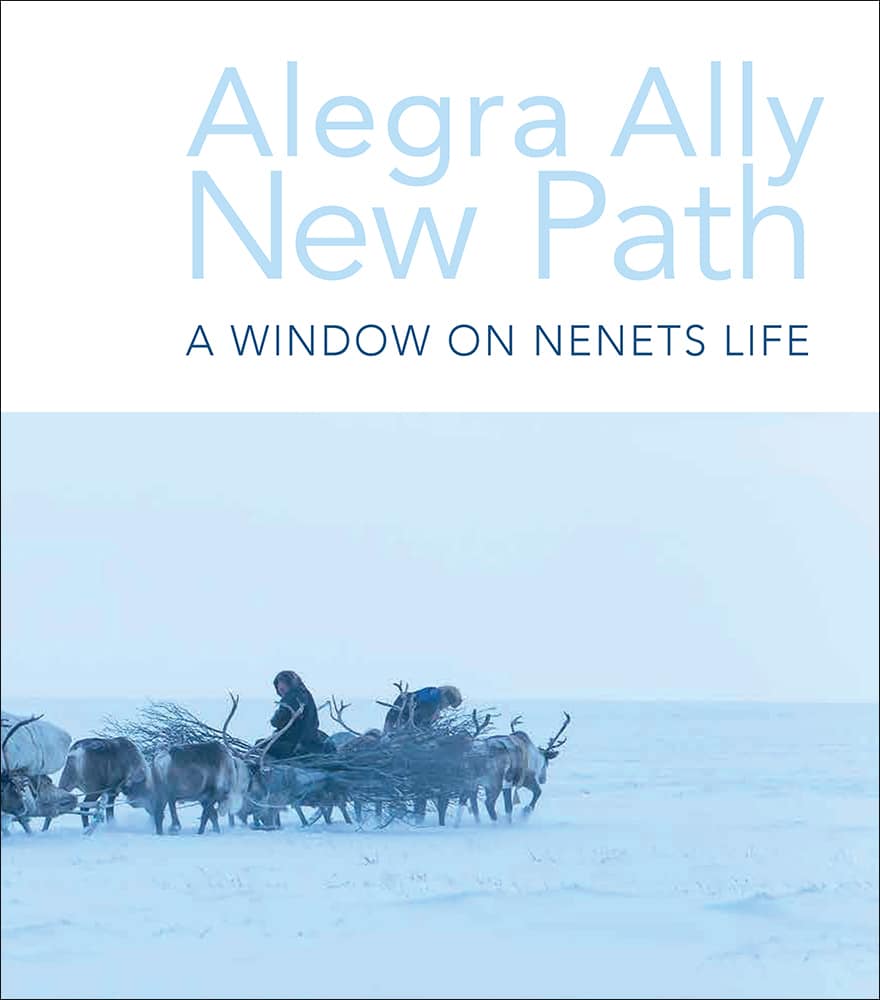

The sleds are an important aspect of the Nenets way of life. They are used for all aspects of their travel and migration, as well as for storage. There are at least two sleds designated for food storage. Like portable refrigerators, these sleds are used to store frozen meat, bread, butter, and other staples.The chum must also be completely disassembled and packed onto the sleds before the family can begin their migration. Everything is tied tightly with rope and then covered by a waterproof layer of reindeer fur and skin and other waterproof sheets. Lastly, the reindeer are tied to the sleds.Set in a line, the sleds form a caravan, with Lyonya at the front.

The Nentsy, like any culture, are constantly changing, though it may not seem immediately apparent.

The sleds are an important aspect of the Nenets way of life.

They are used for all aspects of their travel and migration, as well as for storage.

Lena (on the photo) lives with her husband Lyonya, their four-year-old daughter Christina and their three dogs, Khutyu, Khadak and Tewa.Finding Lena, a nomadic Nenets woman who was close to giving birth, was a challenge for photographer and ethnographer Alegra Ally. The journey with Lena and her family took many unexpected turns. Lena gave birth during an extremely challenging season where winter migration did not go as planned. The birth saga came to be emblematic of the Nenets’ struggle to keep their cultural heritage and highly adapted way of life intact in this modern age.

There are at least two sleds designated for food storage.

What initially drew you to this topic?

The journey with Lena and her family took many unexpected turns.

For thousands of years, indigenous Nenets have led nomadic lifestyles, migrating with their reindeer herds across the Yamal Peninsula in the Russian Arctic. The Khudi family is one of 12,000 Nenets still migrating along the same routes as their ancestors did for centuries.Unfortunately, because of the climate change, which harshly affects weather conditions in the tundra, thousands of reindeer died of starvation in the Yamal Peninsula two years ago. Lyonya explains, “We had rain in the middle of February, which turned the tundra into a sheet of ice. Our reindeer suffered because they couldn’t dig the ice to get lichen. That year my uncle lost more than 400 reindeer.”

Lena gave birth during an extremely challenging season where winter migration did not go as planned.

Planning this expedition logistically was complex, and required research and planning for a year prior to my departure.

The Yamal peninsula is remote and accessibility is challenging.

During the change of season from autumn to winter, the vast tundra of the Yamal Peninsula is transformed into an icy landscape covered in snow and interlaced with frozen rivers and lakes. This transformation allows the Nentsy to migrate with their sleds and reindeer herds across the tundra for thousands of kilometers, following their ancient migration route to their winter camps.In autumn 2016 winter was late to arrive, and the absence of snow made it impossible for the Khudi family to begin the migration. Uncommonly warm temperatures and unstable weather patterns that have temperatures rising and falling dramatically created a muddy wetland that is unstable and treacherous for the reindeer to traverse. The waterlogged soil is also bad for the vegetation, particularly the lichen that grows here, which is starting to deteriorate. The lichen is the primary food source for the reindeer, and the reindeer are the reason for the Nenets way of life.Climate change has a strong impact on the Nentsy, their herds, their migration, and their adaptation to the new reality.

More so, the Nenets are on a constant move and very difficult to reach.

I had to work with a local fixer who is known amongst Nenets families.

The fact that a family accepted me into their midst is something I appreciate greatly.

A huge part of the Nentsy’s adaptation to life on the tundra lies in the ingenious design of the chum, the traditional tepee structure that they live in.Withstanding frost, heavy snowstorms, and strong winds, it keeps the family safe and comfortable in all imaginable elements. The chum we stayed in is made up of twenty-two pine poles and is adapted to the different seasons on the tundra through the coverings used on the outside and the flooring laid out on the inside. There is a gap at the top for ventilation and to allow smoke to escape. In spring and summer, there are two layers of felt fabrics enclosing the structure. In autumn the chum is covered with two layers of reindeer skin and fur, each layer stitched from between twenty-five and forty skins. The flooring of the chum in summer is usually a thin plastic layer, in winter this is covered by wooden flooring, which is often layered again with reindeer furs.

I think there is a universal law between hosts and guests.

Respecting boundaries and being sensitive to their culture was essential.

I constantly felt humbled by their generosity and sharing and it made me be constantly grateful.

Praskovya is 96 years old, and the oldest Nenets grandmother living on the tundra. Even at 96, her age does not stop her from spending many hours outside, helping with the herd, and cutting firewood.In particular, she loves her Laika working dogs and is very affectionate with them. She is also a great storyteller, sharing her stories with the family, passing on words of wisdom, and knowledge she has gained. The stories she tells are oral textbooks, containing lessons, ideas, and guidance on how to protect, respect and preserve the connection the Nentsy have with their land, culture, and values.

Our reindeer suffered because they couldnt dig the ice to get lichen.

That year my uncle lost more than 400 reindeer.

It was a difficult winter that you encountered.

In the Nenets culture, all jobs inside the chum, including all of the house-keeping, cooking and taking care of the children and the dogs, are done by women, while men’s responsibilities are with the herd. Men are prohibited from doing any of the women’s work.In her free time, Lena sews and decorates boots, gloves and winter apparel using dried reindeer sinew as thread. Four-year-old Christina accompanies Lena as she goes about all of her daily chores and tasks. The bond between a mother and a daughter is very strong, especially given that the family lives in relative isolation from other families, a fact that defines much of the Nentsy’s unique identity.

What did this teach you about the character of the Nenets and their resilience?

The Nenets are masters of adaptation and we can all learn from them about resilience.

There is a gap at the top for ventilation and to allow smoke to escape.

The most basic aspects of survival, such as keeping warm, requires constant tending to here on the tundra. Cutting firewood to keep the fire burning, or using an ax to break the ice to fetch water for cooking and drinking, are daily tasks that must be done in all kinds of weather, including snowstorms and temperatures of -40 to -50°C.For the Nentsy, most of these daily tasks for survival and comfort are the responsibility of women in the family, whereas the men tend to the herd. Lena is nine months pregnant but she still follows her daily patterns and fulfills the tasks she is responsible for.

In spring and summer, there are two layers of felt fabrics enclosing the structure.

Did you have a specific creative plan in mind going into the experience?

And how did that change as the adventure developed?

For the four-year-old Christina, the vast open landscape of the tundra in autumn is her playground, and she makes a game of breaking the thin ice that forms over the pools of water. Gradually as the winter comes, the air becomes crisper and temperatures begin to drop consistently. The layers of ice begin to thicken and Christina finds great joy in rolling on the thick frozen ice.The extreme weather conditions due to climate change were unfamiliar to the Nentsy until recently, and have also had an impact on the people’s health in the tundra. When temperatures suddenly change from -5 to -35°C in a matter of days, it puts a tremendous strain on the human body. During this period of erratic weather, Christina experienced multiple nose bleeds, and one herder collapsed.

For example; in Siberia, the element of climate change became a dominant part of the story.

Initially, my plan was to migrate with the family several times during the 60 days.

So instead of photographing their migration, I photographed the family and their reindeer on patches of muddy soil.

The dogs are treated like family in the Nentsy culture. Lena and her husband Lyonya have a herd of 800 reindeers and three, who are an essential part of herding reindeer.The Nenets rhythm of life is determined by their herds. It is the reindeer’s pasturing needs that set the movement of their human owners in motion, but it is the humans who lead the migration across the tundra. While the men are lassoing the herd, women help by keeping the herd together. For several hours, Lena’s role is to circle the herd over and over again with one of the dogs at the end of a long leash until the lassoing is finished. Circling a herd of about 800 reindeer is a big distance to cover, and the dogs bark and try to run, pulling at the leash enthusiastically, making Lena work even harder to control them. It is extremely tiring and physical work that requires constant attention.

My journey with Lena and her family took many unexpected turns.

Praskovya is 96 years old, and the oldest Nenets grandmother living on the tundra.

Can you talk about the impactboth emotional and physicalof living in that extreme cold?

My main challenges are both physical and physiological.

One big challenge, which people often are not aware of, is loneliness.

It is a complicated issue, but learning to embrace it and not resist allows for immense personal growth.

I can say that I mostly enjoy the challenge and appreciate it.

Four-year-old Christina accompanies Lena as she goes about all of her daily chores and tasks.

What do you admire most about Lena and what do you hope that people take away from her story?

There are so many things I admire in Lena.

As a mother, a wife, and a woman, and as a host.

For all the hardship, Lena did not express any desire to change her way of life.

That all societies should become us.

None of them is more or less of an ideal.

Cultural diversity is our only hope for keeping the human spirit alive.

Gradually as the winter comes, the air becomes crisper and temperatures begin to drop consistently.

During this period of erratic weather, Christina experienced multiple nose bleeds, and one herder collapsed.

What’s next for you?

We have launched the 2020 passage expedition to Papua New Guinea.

The dogs are treated like family in the Nentsy culture.

While the men are lassoing the herd, women help by keeping the herd together.

It is extremely tiring and physical work that requires constant attention.

We believe much can be learned from traditional midwives.

We are here to learn, share knowledge and co-create programs with these women.