Crafted in the early 16th century, this pair of sculptures were originally part of a papal commission.

They presented Michelangelo with a second contract detailing a smaller, subdued version of the tomb.

To make matters worse, these ever-changing plans ended up omitting some of Michelangelo’s nearly completed sculpturesincluding theSlaves.

Photo:Flickr(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Both, however, exhibit markers of Michelangelo’s signature skill: a lifelike approach to the human form.

Then, they found a home in Cardinal Richelieu’s palace in Poitou.

As the Louvre’s only Michelangelo marbles, they are arguably his most famousSlaves.

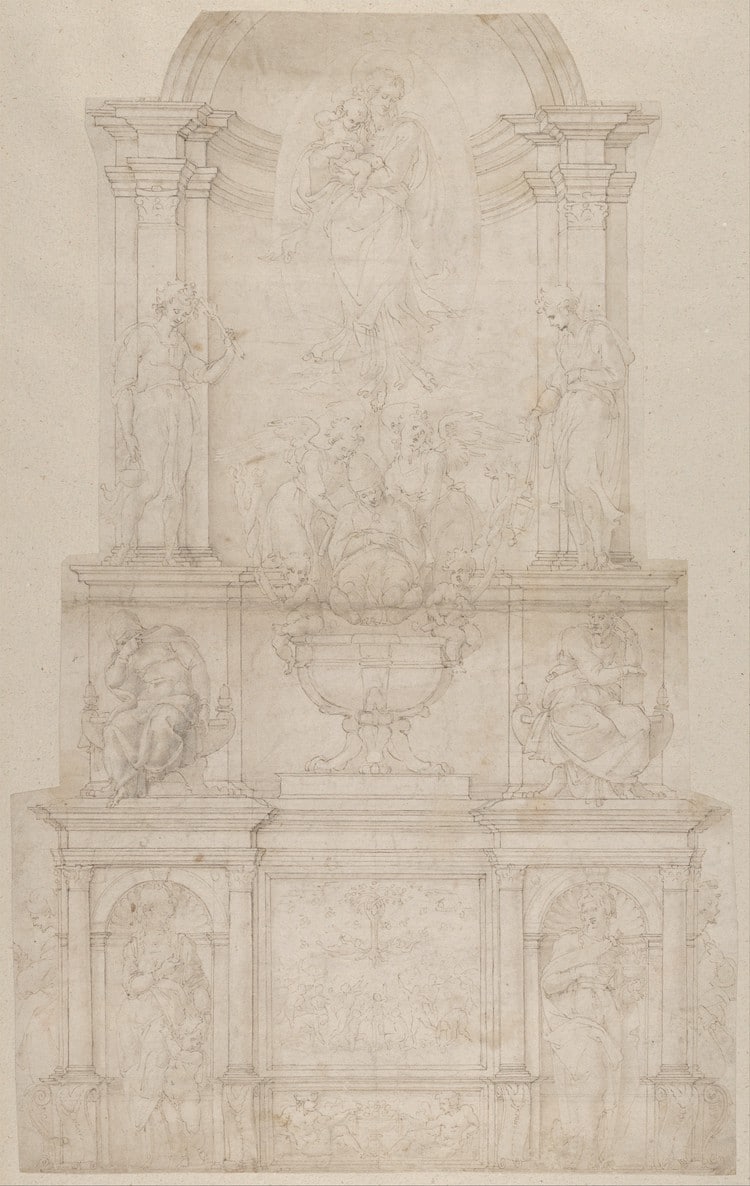

Michelangelo, “Design for the Tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere,” 1505-1506 (Photo:The Metropolitan Museum of Art[Public Domain])

They aren’t, however, the only ones.

I saw the angel in the marble, Michelangelo once remarked, and carved until I set him free.

Horace Vernet, “Julius II Ordering Bramante, Michelangelo, and Raphael to Build the Vatican and Saint Peter’s,” 1827 (Photo:Wikimedia Commons[Public Domain])

(Left Photo:Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 3.0]; Right Photo:Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 3.0])

Michelangelo, “Studies for the Sistine Ceiling and for the Tomb of Pope Julius II” (Photo:Wikimedia Commons[Public Domain])

Photo:Stock Photosfrom Heracles Kritikos/Shutterstock