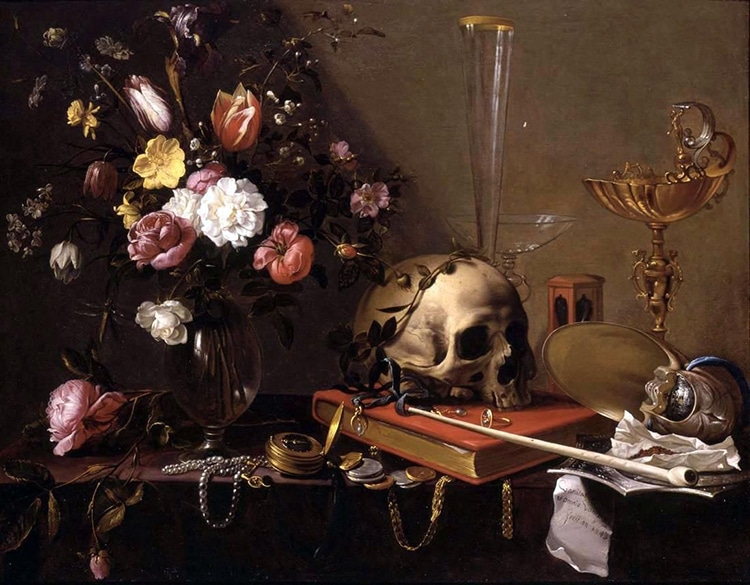

Allegory of Vanity, by Antonio de Pereda, circa 1632 1636.

(Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

What does a skull symbolize?

Many people would say death or danger, pointing to the classic skull-and-crossbones pirate flag.

“Allegory of Vanity,” by Antonio de Pereda, circa 1632 – 1636. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Others might think first of skulls in a scientific contextan evolutionary trail leading humans to our modern form.

However, vanitas paintings are not all doom and gloom.

Instead, they encouraged a more pious, spiritual approach to life.

A Roman mosaic “memento mori” from Pompeii, showing the Wheel of Fortune and life and death both hanging by a thread. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Those viewing an early modern vanitas painting were encouraged to live their lives transcendent of earthly concerns.

(Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The ancient Greeks and Romans thought a lot about death.

Amemento moriserved as a physical reminder of this truth.

“A vanitas portrait of a lady,” Clara Peeters, circa 1613-1620. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

These tokens are literal embodiments of their Latin name, meaning remember that you will die.

Such a reminder could take the form of a mosaic.

Medieval Europeanscombined Christian theologywith the stoic legacy to put their own spin onmemento mori.

“Vanitas—Still Life with Bouquet and Skull,” by Adriaen van Utrecht, circa 1642. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Dutch Golden Age

A vanitas portrait of a lady, Clara Peeters, circa 1613-1620.

The Golden Age spans the 17th century when trade allowed the Netherlands to flourish.

Art and culture thrived under the prosperous patronage of merchants and nobles.

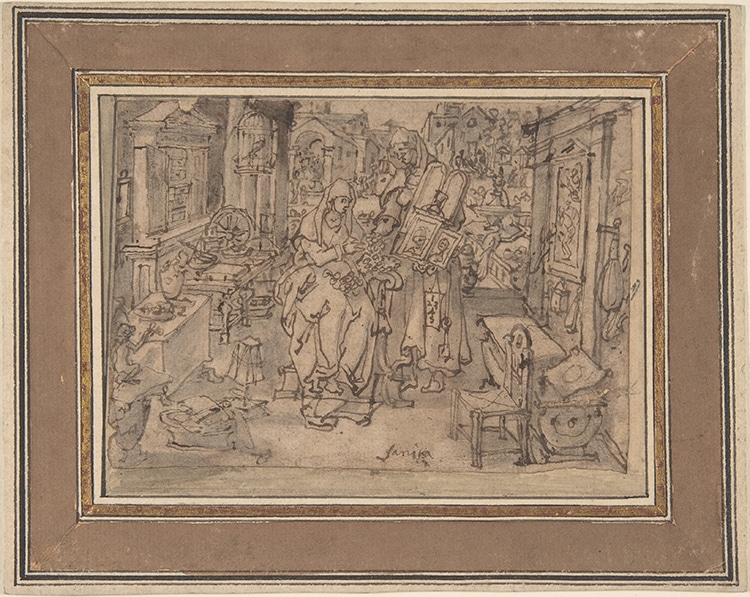

“Vanitas,” by Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, mid-16th to early-17th century. (Photo:The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The birthplace of Rembrandt, the city was also a center of theDutch Renaissance.

Theology and artistic tradition would come together to produce countless well-known examples of vanitas paintings.

Like memento mori artwork,skullsfeature prominently, as do hourglasses and withering vegetation.

“Allegory of Charles I of England and Henrietta of France in a Vanitas Still Life,” anonymous Flemish painter, 1670s. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

These carry the same meaninglife is short and fleeting.

However, as noted by theTate, vanitas paintings add a moreworldly symbolism.

Vanitas, by Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, mid-16th to early-17th century.

“Skull Portraits,” by Alexander de Cadenet, on view at 30 Underwood Street Gallery, Shoreditch, London March 2000. (Photo: Saffarelli viaWikimedia Commons,CC BY-SA 4.0)

Instead, the viewer is encouraged to contemplate the eternal afterlife as described in Christian theology.

Protestant painters produced many of the most well-known vanitas works.

However,Catholic artistscontemplated these same themes as well.

“Still-Life with a Skull, Vanitas,” by Philippe de Champaigne, circa 1671. (Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

While not a strictly cheerful message, all hope was not lost for the pious.

(Photo:Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Vanitas works are an example ofallegorical art.

An allegorical work may be figurative orstill life, however, its true meaning goes beyond what is depicted.

The subject of the work is used to represent a higher ideal or idea.

Thesehidden meaningsmay sometimes seem obscure to the contemporary viewer.

Most enduring is the skull, still today a symbol of death.

The teeth are real human teeth.

The work debuted in 2007 to much comment in the art world.

Art is arguably about life, and commenting on death is not new.

The vanitas tradition continued the meditation of life and death that had long existed in memento moris.

No matter how transient this life, the paintings illustrate, there is something higher to aspire towards.

Still-Life with a Skull, Vanitas, by Philippe de Champaigne, circa 1671.